To fulfil its twin ambitions of creating a competitive national market for electricity and achieving a rational balance between total generating capacity and regional load, China needs a nationwide network of fully interconnected regional grids. Achieving it has become a concrete long term aim of the government. The current plan includes several high capacity long distance lines (in the order of 1000 km) as well as grid interconnectors. For reasons mainly of power economy and to overcome inter-grid asynchronicity the chosen technology is largely HVDC.

Grid interconnection (Figures 1 and 2, Table 1) is being attempted against a backcloth of investor uncertainty, a market that is uncompetitive because of the lack of opportunities for inter-regional flow, a financial structure under which supply and pricing are controlled by grid operators and political direction that has seen grid income from generators diverted away from infrastructure creation in recent years. Moreover statistics and marketing data are fragmented, unreliable and difficult to gather. When a consumer market develops, it is likely to be hampered initially by the lack of reliable marketing information.

One aspect is not in doubt. By whichever indicator you choose – general economic growth, energy investment, or T & D investment plans – the electricity market is already large and growing at a phenomenal rate.

The figures themselves are staggering, although they tend to vary somewhat depending on whether the source is the World Bank, the national government or one of the several other investment agencies, such as the Asian Development Bank, that operate extensively in China. But according to the World Bank, the country’s electricity investment is expected to reach US$60 billion per year over the next 30 years. More than a third of it is for expenditure on the transmission system.

Political and economic factors

China’s own figure for total planned investment in the power sector over the next 30 years is $2.5 trillion, more than any other region in the world. 60% of that will be in power generation, 37% in transmission, and 3% in refurbishment. The International Energy Agency puts the figure a little lower, at $2 trillion, with half going into transmission and distribution.

The source of funding on this scale is far from clear, however. Investment from the private sector has fallen off sharply since 1997 to around US$5 billion per year, in part due to the need for cost-reflective pricing, and other reforms in the power industry, including an integrated competitive market that would handicap producers of more expensive power, a group that includes foreign owned plants. Project owners must seek to raise capital despite offering rates of return that are capped by the State Development Planning Commission at “slightly above” the cost of capital. Examples of disadvantageous repricing abound, such as Meizhou Wan, a wholly foreign-owned 720 MW clean coal plant, which had to renegotiate its power purchase agreement with Fujian authorities after they reneged on their previous agreement of 0.56 yuan (6.8$cents) per kWh and offered prices of 0.44 yuan to customers.

In the late nineties, China experienced an oversupply of electricity, owing to the closing of numerous unprofitable state-owned enterprises at that time. There followed a moratorium on new power plants until 2002. Supply was able to keep up with demand, as there was still a backlog of projects approved prior to the moratorium. In the first half of 2003, the government approved some 30 new power plant projects in an attempt to catch up with rising demand, as the industrial sector was again booming.

A major issue for generators, however, is distribution. China’s high elev-

ations in the west give rise to large amounts of hydro power, in an area with low industrial concentration. The north is also oversupplied compared to the south and eastern provinces. Of the total power consumption in year 2000 of 1300 TWh, 50% was consumed in eastern and southern coastal provinces, but only 12% and 6% in southwest and northwest provinces. However, transmission from one region to another accounted for less than 1.6 % of China’s total distribution in 2001 owing to fragile grid networks.

The State Grid Corporation has stated that it will invest $9.8 billion in transmission and distribution this year, despite its self-admitted lack of funds. The companies have spent more than 300 billion yuan (US$36.3 billion) in recent years to improve power grids in rural and urban areas. Most of the cash was borrowed from State banks, and was due to be paid back during a term starting in 2003. This leaves them searching for new sources of investment, as the current State tariff system gives 60% of revenue to generators to attract investors for power plants. The State Grid previously used the revenue from the generating plants to finance the construction of the grids, but these have been offloaded since the restructuring of the State Power Corporation in 2002 to promote competition and reform in the sector.

So cash strapped grid companies are having to consider new fundraising plans, which could include listing on domestic or overseas stock markets. But the listing plan will stay a long way off until the government reforms the electricity pricing scheme to improve profitability for companies and loosen restrictions on private and foreign capital to the strictly controlled grid networks. A research report by J P Morgan and backed by the State Council indicates that the two grid corporations have been saddled with insufficient capital, large debts (currently running at 61 % of assets) and insufficient means to generate cash flow.

The annual cash flow of the State Grid Corp, the larger of the two, is estimated at about 33-35 billion yuan (US$4.0-4.2 billion) for 2004-10, should the current electricity pricing system remains unchanged. It only accounts for 38 per cent of planned investment in building and improving the grid networks during that period. Southern Grid Corp faces a similar financial situation.

Media reports indicate that the State Grid aims to float on the stock markets by 2008. But the prospect of new cash flow may remain hypothetical. One problem is that the government still places transmission assets off-limits to foreign capital, because it considers them strategically essential for the nation’s economic welfare. Another is cash flow – the State Grid Corp last year posted a net profit of 4.2 billion yuan (US$507.8 million) with a turnover of 427.7 billion, a return of just below 1% compared to 4-7 % for power grid companies in most industrialised countries. Weak profitability is mainly owing to the current pricing system, which favours generating firms.

Central government is reluctant to raise consumer prices, but is apparently mulling over a plan to do so, according to an official news source. And the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) is said to be looking at lifting the current price by an average of 0.02 yuan (0.24 US cent) per kWh, in part to help finance the strengthening of vulnerable transmission lines.

Supply-demand imbalance

From the second half of 2002 China’s electricity supply was far short of demand because of dry spells that put hydroelectric supply out of commission, a generator shortage, and unexpected demand from energy-intensive industries. During the intervening period twenty-one provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions in China have suffered large-scale electricity shortages. Some had to implement blackouts to limit electricity consumption. Heihe City in northeast China has been forced to make contracts to import electricity (15.4 billion kWh over ten years) from Russia, the first time China has done this, to meet increasing demand.

China Electricity Council (CEC) forecasts that the electricity supply and demand situation will be even tighter during 2004 and that the power supply problem will linger on through 2005. It estimates that supply and demand will reach equilibrium during 2006.

Industry watchdog the State Electricity Regulatory Commission has predicted that the country’s generating capacity will fall short by 20 GW this year, 5GW more than last year’s figure. Experts from the State Grid Corp, which oversees most of China’s transmission assets, are more pessimistic. They anticipate that the supply-demand gap could be as much as 30 000 MW if the increase in consumption reaches 12%, the high end of the expected range. China’s energy needs are forecast to increase more than 7% per year over the next 30 years, with the residential and commercial sector increasing from the current 24% share to as much as 44% by 2010.

To lower the costs of production and achieve a proper hydro/thermal power mix, the government intends that its improvement of grid interconnections should optimise available generating capacity, and ‘rationalise’ inefficient coal-fired power plants. The Tenth Five Year Plan will promote more environment-friendly power generation including hydropower development in the western region and investments in the inter-provincial and inter-regional transmission connections. Consequently, Government approval of new power generation projects will emphasise the need to transmit power from west to east.

.

China’s T & D future

China is becoming the world’s largest HVDC user. By 2010, with the completion of Three Gorges hydropower station (22.4 GW), power grid connections in China will have been strengthened by the completion of several HV lines, including the current spate of construction, mainly to carry power from central China to the coastal industrial regions, and by the consequent asynchronous connection of the CC, EC and CS grids.

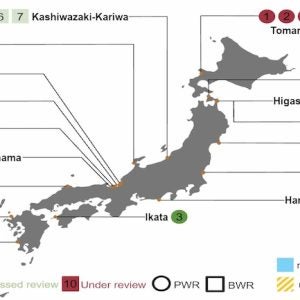

Figure 2 and Table 2 show the regional grids, together with their salient characteristics. As well as the seven provincial grids (North China, Northeast, East China, Central China, Northwest, Sichuan and Chongqing, and Southern) there are five smaller independent grids – Shandong, Fujian, Hainan island, Tibet and Xinjiang.

The current plan to 2020 envisages a series of inter-grid linking steps as follows:

• By combining CCPG, ECPG and CSPG, the Central Power Grid (CPG) will be formed.

• Alongside development of the coal power base in north China, the interconnection between NCPG and NECPG is to be strengthened; the Shandong Provincial Power Grid (SPPG) will be connected to NCPG.

• Then the North Power Grid (NPG) combining NWCPG, NECPG, SPPG, with NCPG as the core will be formed.

• With the development of the hydropower stations of Longtan and Xiaowan in the southwest, and coal power stations in Guizhou province, connections within SCPG will be strengthened; the South Power Grid (SPG) will be formed. By this time, three inter-regional power grids, the North, the Central and the South, will have been formed.

• By 2020 interconnections between North, Central and the South Power Grids are to be further strengthened, resulting in a nationwide integrated power grid in China with the Central Power Grid as its core.

At least 16 and maybe as many as 24 major HVDC interconnectors will be created during the realisation of this plan, possibly including DC lines of around 2000 km at voltages higher even than the Itaipu (Brazil) link, at 600 kV the current world record-holder. There is also a plan to step up voltage in the NW network to 750 kV. Work has already started on a 750 kV AC line from Manping to Lanzhou.

The need to distribute the vast output of Three Gorges, Gezhouba and future hydro plants planned for the Yangste is providing much of the impetus for transmission build. Power will ultimately be exported via 15 lines – more than 6000 km of 500 kV AC lines to Central China and Chongqing, as well as the 4000 km of ±500 kV DC lines to east and south China described above.

But transmitting the output of the Guizhou coal and central China hydro plants will not on its own solve the east-west imbalance. The greater plan describes three principal routes. In the north, 5000 MW of carrying capacity is to be constructed between the Shanxi-Inner Mongolia and Jinjingtang areas; in central China 9000 MW of lines from Sichuan to the east coast are to be constructed, including the second Three Gorges to Shanghai bipole; while in the south 10 000 MW of capacity is ultimately to be built from Guizhou and Yunnan provinces to Guangdong.

THIS PANEL ONLY IF THERE IS ROOM

Regulation

The State Electricity Regulatory Commission was set up in 2003 to oversee and regulate liberalisation. But there is doubt even in official circles about its ability to oversee the process effectively. The general opinion seems to be that the commission lacks the necessary authority.

Yu Yanshan, an official with the commission’s policy and regulations department, has said that important roles such as approving electricity prices and the construction of power plants are scattered among government departments, including the National Development and Reform Commission and the Ministry of Finance, which has diminished the industry watchdog’s clout, and that the obligation of government departments and the commission is not clear. He has called for consolidation among government departments and the commission as soon as possible to better regulate the industry.

End of panel

The players

ABB, Siemens, Moeller, GE, and Schneider all have a strong presence in China and ‘new’ T & D entry Areva (formerly Alstom) is busy establishing one. Siemens, GE and ABB in particular have strong networks of manufacturing, engineering and support facilities in the country and all enjoy a technological lead over indigenous companies. ABB and Siemens have built or are building the long distance HV lines carrying power to the industrial south and south-east. In June 2004 ABB handed over to the State Grid Corporation the second of these – the 975 km Three Gorges-Guangdong HVDC link, ahead of schedule and after a construction time 19 months shorter than its 3G-Changzhou link.

For components – panels, transformers etc – the picture becomes less clear. All the big players added together probably have less than 35% of the market while hundreds or in some market areas thousands of local Chinese companies have the rest. For example in LV panels – part of an LV market of unknown size but estimated at between 1.25 and 5 billion US$ – there are more than 2000 Chinese companies listed. ABB has the largest share and it has only 4% or so.

Unsurprisingly the market price for a substantial proportion of electrical equipment has been dropping by 5-10% year on year for the last 5 years, but Chinese manufacturers are still able to improve their quality at a fast rate. Quality is a short-term advantage for foreign manufacturers. Only in high technology, for example in ‘intelligent’ switchgear, can the big players maintain a long-term lead.

The new order

To end it’s monopoly of the power industry, China’s State Council dismantled the State Power Corporation (SPC) in December 2002 and set up 11 smaller companies. SPC had owned 46 % of the country’s electrical generation assets and 90 % of the electrical supply assets. The new smaller companies include two electric power grid operators (the State Grid Corporation and the China Southern Power Grid Corp) supervising the dozen regional networks (see Figure 2), five electric power generation companies and four relevant business companies. Current and ongoing reforms aim to separate power plants from power-supply networks, privatise a significant amount of state-owned property, and rewrite pricing mechanisms.

In March 2003 State Council established the State Electricity Regulatory Commission, the first supervisory body for China’s basic industries. The Commission is to carry out a structural reform of the power industry, speed up the construction of laws and regulations, develop an electrical supply trading market, and establish a supervisory organisation. However, important roles such as approving electricity prices and the construction of power plants are scattered among government departments, including the National Development and Reform Commission and the Ministry of Finance, which has diminished the SERC’s clout. One of its officials, Yu Yanshan, has called for consolidation among government departments and the commission as a matter of urgency, because ‘the obligation of government departments and the commission is not clear’.

After several years of poor growth, investment in China’s power industry is regaining momentum. Official statistics show power consumption growth in China averaging 7.8% annually throughout the 1990’s. China’s electricity consumption reached 1891 billion kWh in 2003, up 15.4 percent over 2002, while its output reached 1908 billion kWh, up 15.3 percent over 2002. According to the International Energy Agency, to meet rapidly-growing electricity demand, China will need to and plans to invest a total of nearly 2 trillion U.S. dollars in electricity generation, transmission, and distribution in the next 30 years. Half of the amount will be invested in power generation, the other half will go to transmission and distribution.

Nonetheless experts disagree as to the wisdom of investing in China’s power sector, for reasons concerning pricing regulations and regional authorities’ history of not honouring agreements.

The impact of what happened at the Meizhou Wan plant, one of three similar cases, has certainly been damaging. The project was China’s first wholly foreign-owned power plant, and regarded by many power industry experts as a potential model for foreign involvement in the domestic power industry. The SDPC approved the pricing structure of the project, as did the Fujian authorities responsible for buying the power. Some of the world’s largest power industry players are consortium members. These include the Asian Development Bank, which has lent China more than $10bn and InterGen, the Shell-Bechtel joint venture which runs 12 230MW worldwide. ADD WHAT HAPPENED

However, with such a large amount of development necessary over the next thirty years, many companies feel confident enough in the market to justify the risk to their investors. Moreover, State banks have been instructed to finance as much as possible of the scheduled reforms in the power grids. And reputedly, local banks have plenty of funds to lend on easier and cheaper terms. It may be that China currently neither needs nor can support the complexities of project finance in the power sector.

Tables

Table 1. Major HVDC components in the national interconnection network

Table 2. Chinese regional power grids.