carbon dioxide

Making CCS commercial by 2020

1 December 2008Why do we need a European demonstration programme and what should it consist of?

The EU has made its position on CO2 capture and storage (CCS) very clear: as a critical solution to combating climate change, its wide-scale deployment is essential. Without CCS, the EU’s CO2 emission targets are simply not achievable.

In March 2007, the European Council (heads of state) confirmed that up to 12 demonstration projects should be operational by 2015 to ensure CCS is commercially viable by 2020. While delivering operational demonstration projects by 2015 represents a significant challenge for industry, it has responded positively through the intermediary of the European Technology Platform for Zero Emission Fossil Fuel Power Plants (ZEP).

ZEP was founded in 2005, bringing together a unique and broad coalition of stakeholders, including European utilities, petroleum companies, equipment suppliers, scientists, geologists and environmental NGOs. As a European Technology Platform, ZEP’s role is to define a strategic agenda for the development and deployment of technologies involving major economic or societal challenges, and share their findings and recommendations with the European Commission to feed into the EU decision-making process.

With over 200 people in 19 different countries contributing to ZEP’s work, the platform’s board consists of 35 different companies and organisations, all dedicated to enabling CCS to become commercially viable by 2020. On 10 November 2008, ZEP delivered a ground-breaking report designed to achieve this goal. Entitled EU demonstration programme for CO2 capture and storage – ZEP’s proposal, the report provides a detailed picture of such a programme and why it is needed: to validate the technology behind CCS; to explore and bring down costs and reduce risks; and to contribute to public acceptance of CCS.

ZEP consulted an extensive range of experts and stakeholders on every aspect of CCS demonstration to establish the optimal portfolio of projects across Europe necessary to cover a full range of CCS technologies and fuel types, geographies and geologies.

It means implementing an EU-wide initiative which integrates all aspects of CO2 capture, transport and storage. Without a demonstration programme, the commercialisation of CCS will undoubtedly be delayed - until at least 2030 in Europe.

The principal conclusions reached in the report:

• A total of 10-12 demonstration projects will be required to test a variety of technologies, to reduce costs and risks and to contribute to public understanding and awareness - and CCS projects currently proposed across the EU can satisfy the majority of the criteria that need to be tested.

• In addition to the base cost of the power plants (u10 billion - u12 billion), industry is prepared to take on the commercial and technical risks associated with building the 10-12 integrated demonstration projects. However, a funding gap of u7 billion - u12 billion will remain to meet the costs of building and running the additional equipment for CCS and costs associated with the reduced plant efficiency.

• The contribution of industry to filling this gap will be determined through a rigorous tender process.

• The speeding up of the tendering and permitting process, and creating of an appropriate regulatory climate, is integral to ensuring the EU CCS demonstration programme delivers CCS as a commercially viable technology by 2020.

• EU-wide co-ordination and implementation for the demonstration programme will provide significant advantages, including: the optimisation of a diverse portfolio; facilitation of the rapid and widespread application of CCS in the EU; and the establishment of a tangible European leadership position in the battle against climate change.

Establishing the criteria to select the projects for the EU CCS Demonstration Programme resulted in unprecedented work by experts within ZEP and the wider CCS community. The selection criteria for an EU demonstration programme address all of the links in the CCS value chain and the required context. Specifically, this will require the testing of:

• Various emissions sources, including power plants with different fuels and the CO2 streams from other industries, like steel or cement plants.

• The three primary means of capturing CO2 – pre- and post-combustion and oxyfuel.

• Different modes of transporting CO2 – pipelines on- and offshore and across borders, and transport by ship.

• The two primary means of storing CO2 – depleted oil and gas fields and different saline aquifers.

The proposed method for selecting the optimal projects for an EU demonstration programme is a staged process, which allows for a stepwise selection of the most suitable projects. In this process of selection, three types of criteria are used:

• Eligibility criteria (five in total) – broad set of conditions which any proposal must meet, including ‘if you don’t share knowledge, you can’t be part of the demonstration programme’ and ‘if you don’t perform, you won’t get paid.’

• Portfolio criteria (16 in total) – which must be met by the programme as a whole, eg including a set of different technologies in each of the steps of the CCS value chain, a variety of hard coal and lignite power plants and sufficient geographical spread.

• Project criteria (11 in total) – against which individual projects will assessed, eg. if two projects are equal, a project is preferred over another if it has an earlier operational start date.

Experts within ZEP and the wider CCS community have identified the functional, operational and technical specifications for the technologies that require validation and integration within the CCS value chain. ZEP calls these Technology Blocks (Figure 1), and they cover capture, transport, storage and improvements in plant efficiency and define what needs to be tested, at what scale, in the demonstration programme from a technology point of view.

After having defined what needs to be tested, we designed portfolios able to test all of these elements. Our work concluded that a total of 10-12 demonstration projects (Figure 2) is required to achieve the goal of an EU CCS demonstration programme and make CCS commercially viable by 2020.

To test the implications for a required portfolio, ZEP collected all available information on demonstration projects proposed in the EU & EEA. This resulted in the most comprehensive list available. Starting from the set of building blocks that need to be tested (as developed in the previous step), we then checked those against this project list.

With eight of the currently proposed projects, the vast majority of the criteria can be satisfied. To cover the remaining elements that require testing, ZEP expects an additional 2-4 projects to be required. This includes for example testing of cross-border pipeline, international co-operation (or project in an emerging economy) and different capture technology variants (2 variants per technology).

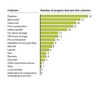

It is worth noting that even before these criteria have been published, 34 projects (Figure 3) have been proposed which are able to fulfil almost all of these projects – a clear indication of their feasibility. These proposed projects are currently awaiting further decisions on funding and legislation.

Knowledge sharing is central to the EU CCS demonstration programme and its desire to accelerate technology development and drive down costs. Indeed, future investment decisions will depend on the experience gained by the demonstration projects, the ability to improve the design and operation of future projects – and build competitive advantage.

Beyond the statutory/ regulatory requirements, ZEP’s EU CCS demonstration programme proposes to offer additional knowledge sharing:

• Public, the government/EU and all entities: general synthesised demo plant findings, including timely disclosure of any safety-related operational issues.

• Entities willing to share relevant knowledge: relevant knowledge on a reciprocal basis.

• Consortia participating in the programme: detailed demonstration plant findings, including timely disclosure of relevant operational data.

It will also facilitate public support for the demonstration programme and enable the effectiveness of public funding to be properly evaluated. Its scope will therefore extend beyond existing national and EU legal requirements (including EU directives).

Following an outline of what the portfolio in the EU CCS demonstration programme would look like, ZEP examined what was required to make it successful:

• Sufficient funding to cover the incremental costs of CCS.

• Appropriate legislation in both EU and Member States.

• Sufficient measures to ensure speed, including fast permitting by local authorities, speeding up of projects by industry, through, eg, starting commercial projects as early as possible during the building of a demonstration project, so that build can begin after one year of the demonstration plant being in operation, accelerating feasibility studies, making faster investment decisions and having a fast tendering process.

CCS is not economically viable today, hence the need to pair public funding with corporate investments. Like all major new technology initiatives, the cost of an EU CCS demonstration programme will be high and unrecoverable, but the programme will be the catalyst to kick-start CCS by delivering experience, technology development and economies of scale which will drive the costs of CCS down.

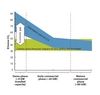

Indeed, the cost of CCS is expected to fall to u35-u50/t of CO2 in the early commercial phase (2020+), when the total installed capacity will be ~20 GW (from u60-u90/t of CO2 currently). A further increase in the installed capacity to ~80 GW will mature the learning curve, after which CCS costs are expected to fall even further to u30-u45/t of CO2. See Figure 4.

Every demonstration plant in the EU CCS demonstration programme plant will face a number of risks associated with their construction and operation, including: building delays; increases in capital and operational expenses; greater than expected efficiency penalty; and, however unlikely, the risk of a major technological failure, leading to the writing off of the entire plant.

Industry is prepared to manage these risks along with the costs for building the actual demonstration plants. In return, public funding is requested to cover the expected incremental costs of CCS (Figure 5). A competitive tender process will incentivise parties to hand in bids with their best offer for risk/cost sharing.

It is helpful to put these costs in perspective: according to the EC, “the costs of meeting a reduction in the region of 30% GHG in 2030 in the EU could be up to 40% higher than with CCS”.

The earlier Europe starts investing in CCS, the greater the benefit it will derive from these investments, until renewables are sufficiently developed to play a fuller role.

The speeding up of the tendering and permitting process is integral to ensuring the demonstration programme delivers CCS as a commercially viable technology by 2020.

While the tender process for participation in the EU CCS demonstration programme must follow certain key steps, those currently underway in Canada and the UK indicate that this could take anything from 9 months to over 2 years respectively, due to the level of detail required from participants and their interaction with government during the process.

An accelerated tender process is essential if an EU CCS demonstration programme is to be up and running by 2015. Taking the best of both the UK and Canada’s proposals, it is estimated that this can be reduced to 15-18 months – excluding the set up of the tender organisation.

ZEP will seek to engage the European Commission and EU member states to identify options and ways to shorten the tender process, without sacrificing quality, to satisfy the timeline for the EU CCS demonstration programme.

The development of CCS recognises the reality that fossil fuels are with us for some time longer and seeks to aggressively diminish their impact on the environment. The potential of CCS is undeniably enormous, requiring that we take a first, bold step towards establishing an EU-wide CCS demonstration programme if we are to make CCS a commercial reality by 2020.

In 2007, the EU first highlighted the need for a CCS demonstration programme of up to 12 projects. Before concluding that 10-12 demonstration projects are required, ZEP worked hard to ensure that its proposal addressed exactly what needs to be tested to ensure CCS is commercially viable by 2020 and the criteria (eligibility, portfolio, project) to select the most appropriate projects

ZEP reached its conclusions through heated and lengthy discussions, often with diametrically opposed views being expressed. These took place between the utilities, petroleum companies, equipment suppliers, scientists, geologists and environmental NGOs that make up our platform.

But if common ground was found between us, then surely it is not a stretch to ask for the support of the EU, member states and the public to ensure that we have one more solution on the table in our bid to reverse the effects of climate change: CO2 capture and storage.